Why Painting "Scary Faces" on Aircraft Engines Doesn't Stop Bird Strikes: A Deep Dive into Avian Physiology and Aviation Safety

Bird strikes cost the aviation industry over $600 million annually, yet one popular "solution"—painting frightening faces on aircraft engines—is largely ineffective. This article examines the scientific evidence, reveals why birds can't avoid collisions despite excellent vision, and identifies what actually works in modern wildlife hazard management.

MITIGATION STRATEGIES AND TECHNOLOGIES

Waleed MAHROUS

11/20/20259 min read

Introduction: The Paradox of Perfect Vision

It seems counterintuitive: birds possess some of the most sophisticated visual systems on Earth, yet they collide with aircraft at staggering rates, an estimated 41,000+ wildlife strikes annually in the United States alone. What's more perplexing is that pilots, airports, and even aircraft manufacturers have tried a surprisingly simple solution: painting scary faces on aircraft engines. All Nippon Airways (ANA) famously deployed this tactic in the 1980s, and the practice persists today on aircraft worldwide. But does it actually work?

The short answer: not effectively, and the science explains why.

This article pulls back the curtain on avian physiology, aviation safety research, and the neurobiology of bird collision avoidance to answer one of aviation's most persistent questions: If birds see so well, why don't they just get out of the way?

Part 1: The Myth of "If You Can See It, You Can Avoid It"

Human Assumptions vs. Avian Reality

We operate under a fundamentally flawed assumption: good eyesight equals good collision avoidance. This works for most animal-to-animal interactions in nature, where predators and prey evolved together over millennia, with collision speeds rarely exceeding 100 km/h. An eagle diving at a rabbit reaches perhaps 200 mph, fast, but not aircraft-fast. It seems that birds are not yet prepared for objects traveling at 300-500+ mph.

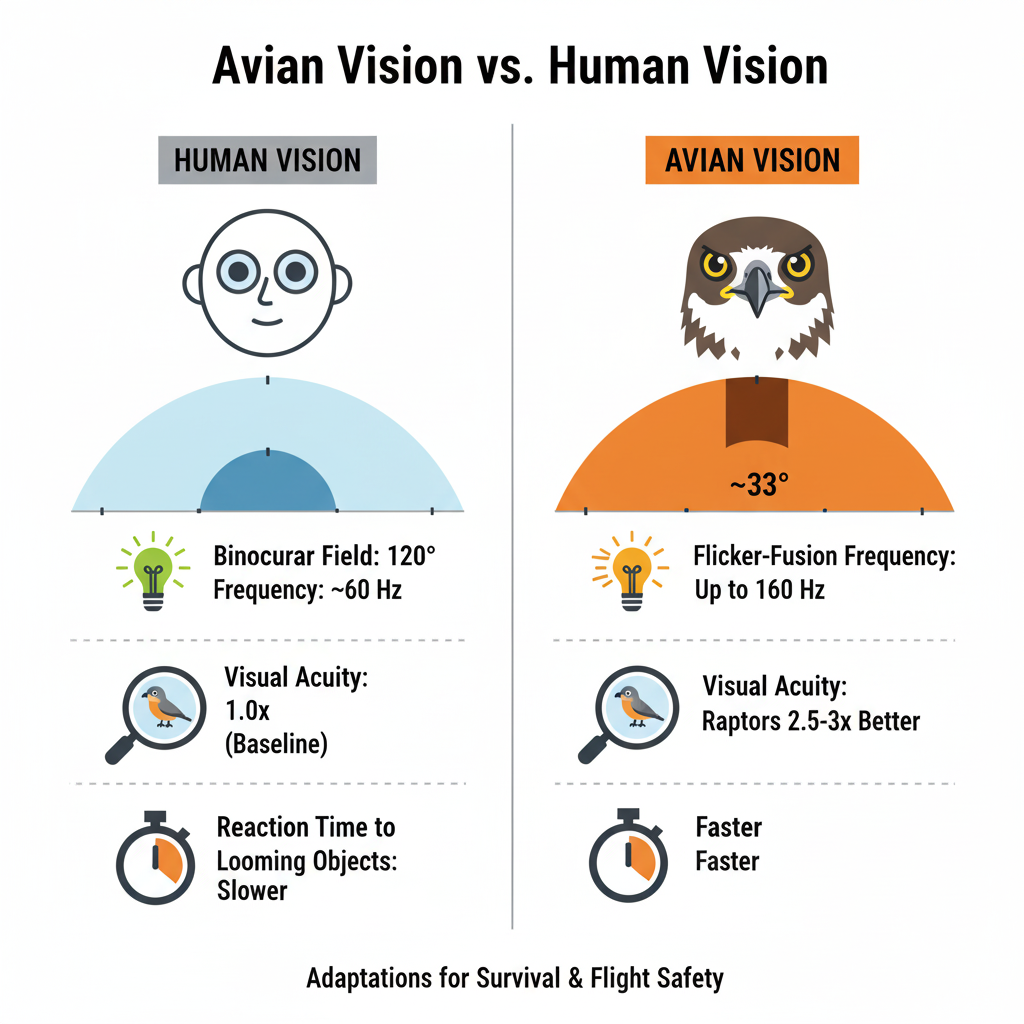

The Numbers: How Good Is Bird Vision Really?

The evidence is impressive:

Raptors possess visual acuity 2-3 times sharper than humans: A wedge-tailed eagle can spot a rabbit from a mile away, a feat impossible for human eyes.

Birds process images at 3-4 times the speed of humans: Where humans perceive smooth motion in a 24 fps movie, birds see a choppy slideshow.

Some birds detect flicker up to 160 Hz, compared to the human flicker-fusion frequency of ~60 Hz: This translates to a temporal resolution advantage of approximately 2.7 times better than human perception.

By any measure, avian vision is extraordinary. Yet extraordinary vision solves only part of the collision problem.

Part 2: The Architecture of Avian Vision, and Its Fatal Flaw

The Tradeoff: Panoramic Vision vs. Depth Perception

Here's the crucial architectural limitation: most birds have eyes positioned on the sides of their heads. This lateral eye placement grants them an almost 360-degree field of view, perfect for spotting predators. But it creates a catastrophic weakness directly in front: a very narrow binocular field where both eyes' vision overlaps.

The numbers tell the story:

Typical bird binocular field: 33-40 degrees compared to humans with ~120 degrees

Starlings and geese have even narrower binocular overlap, sometimes as little as a slit

Why does this matter? Binocular vision is essential for judging the speed and distance of directly approaching objects. Without it, birds cannot accurately estimate how fast something is coming at them.

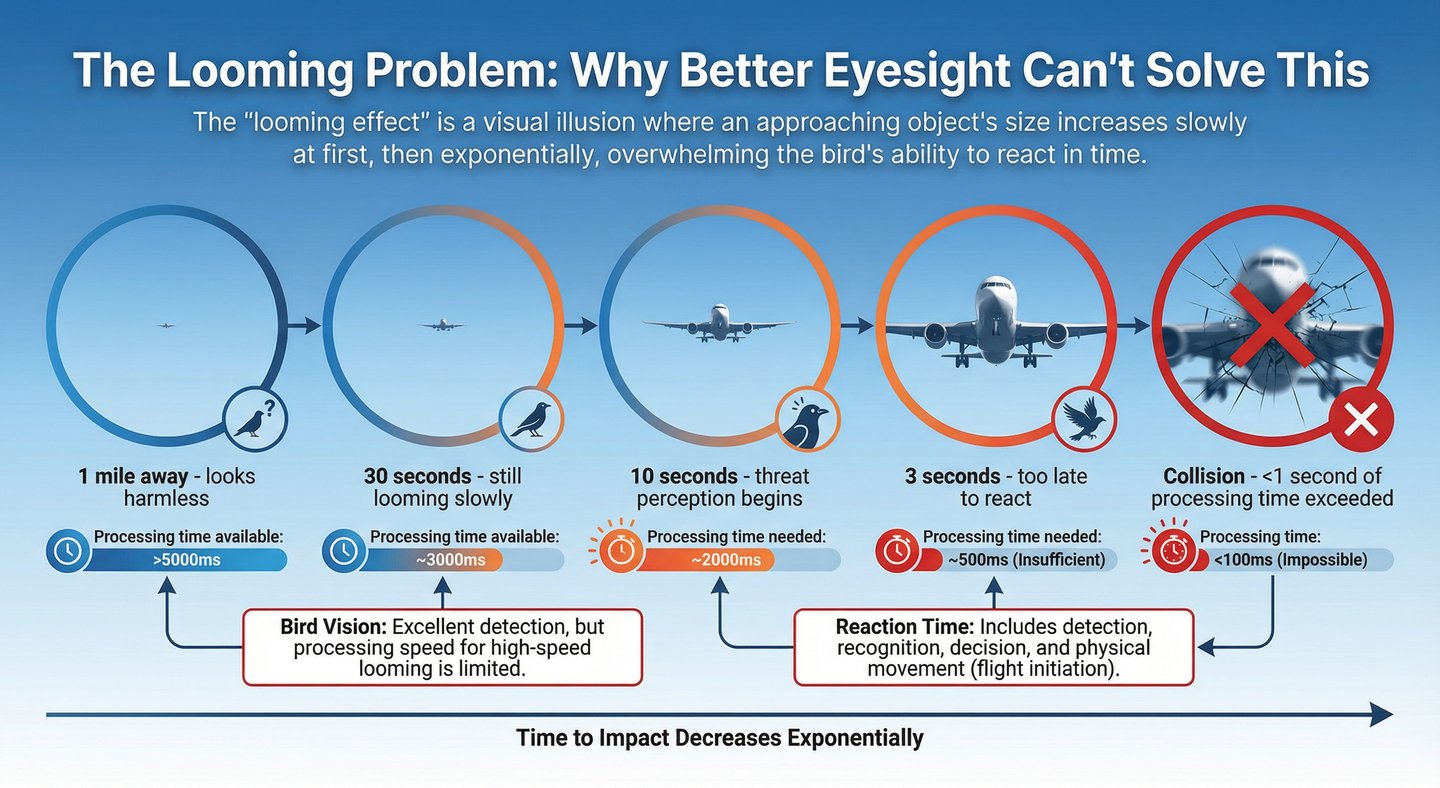

Enter the "Looming Effect"

When an object approaches directly toward you, it doesn't look like it's moving; it just gets bigger. This is the looming effect, and it's a fundamental limitation of visual neurobiology, not intelligence or attentiveness.

For birds, this presents a lethal problem:

An aircraft at 1 mile away appears very small and doesn't trigger urgency.

An aircraft at 30 seconds away still looms slowly enough that it doesn't register as imminent danger.

An aircraft at 5 seconds away has become so large, and the looming has occurred so rapidly, that the bird's brain literally cannot process the incoming threat in the remaining milliseconds.

The Reaction Time Math

Research on turkey vultures and mallards approaching vehicles at high speeds revealed a sobering reality:

At 60 kph (37 mph): 0% near-collisions (collision defined as <1.7 seconds time-to-collision).

At 90 kph (56 mph): 17% near-collisions where birds failed to react appropriately.

An aircraft traveling at 300+ mph faces even worse odds.

Part 3: Why Birds are not - to the best of our knowledge - prepared for this?

The Missing "Threat File"

A bird's brain has been created to recognize and avoid specific threats: hawks, falcons, and snakes. These threats move at speeds the bird's neurobiology can process. They have behaviors that are predictable based on experience.

A commercial jet has none of these properties:

Speed: 300-500+ mph (far beyond anything in their experienced history).

Appearance: A 200-ton metal cylinder (not a hawk or predator).

Behavior: Approaches in a straight line from a predictable direction (unlike a predator's evasive flight patterns).

Size: Massive and unnatural.

The bird's threat-recognition system simply has no "file" for this. It's not that birds are stupid; it's that they lack the neurological template to perceive this as a threat until it's too late.

Part 4: Why Painting Eyes on Engines Can't Solve This

The Intuitive Solution That Fails

Humans recognize faces and interpret facial expressions as signals of threat or friendliness. So it seems reasonable: paint "scary eyes" on an engine, and birds will perceive it as a threatening animal face and avoid it. All Nippon Airways tried this, and they reported approximately a 20% reduction in strikes. Case closed, right?

Not quite.

Problem 1: The Rotation Problem

An aircraft engine spinner rotates at 2,200-4,500 RPM during flight. Let's do the math:

At 4,500 RPM: 75 rotations per second.

At 300 mph airspeed: the engine rotates 75 times while the aircraft covers approximately 440 feet (134 meters).

Bird flicker-fusion frequency: up to 160 Hz (160 distinct images per second).

At this rotation speed, even a bird with flicker-fusion frequencies reaching 160 Hz cannot resolve the painted "eyes" as distinct features. The pattern becomes motion blur—indistinguishable from any other engine.

Problem 2: The Binocular Vision Problem

A bird approaching an aircraft head-on perceives the engine primarily through peripheral (side) vision, not foveal (central) vision:

Peripheral vision in birds excels at motion detection but has lower visual acuity and color perception.

Facial recognition, even of "scary" faces, relies on detailed pattern analysis, a capability of foveal vision.

By the time a bird resolves the pattern enough to recognize it as "scary," the collision window has closed.

Problem 3: The Neurological Pathways

Most critically: birds, as claimed, don't have a response to "scary" human facial features - "Nobody knows but Allah":

Predatory threats in avian history (raptors, snakes) don't resemble painted engine spinners.

The neurological pathways that trigger antipredator responses are not activated by human-designed visual patterns.

You cannot trick a bird into avoiding something it has no template for recognizing as dangerous ➞ (theoretically accepted, but practically?).

Part 5: What Actually Works, Evidence-Based Solutions

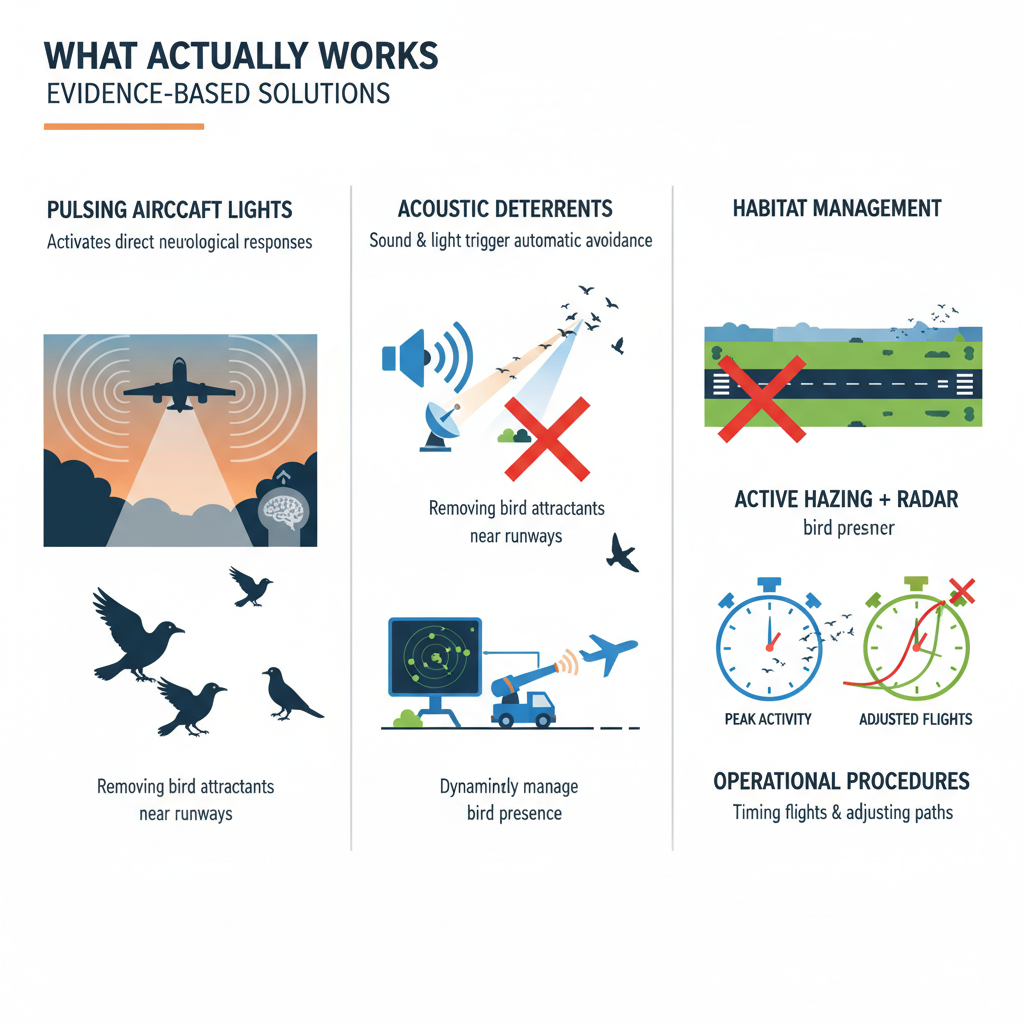

Given that visual fearfulness doesn't solve the problem, what does?

1. Pulsing Aircraft Lights (Proven Effective)

Studies show 91-99% of birds exhibit alert behavior when exposed to pulsing aircraft lights, particularly in low-light conditions. Why? Because pulsing lights activate direct neurological responses related to motion and flicker sensitivity, not learned fear.

2. Acoustic Deterrents (Moderately Effective)

Acoustic signals at 4-6 kHz frequency-modulated frequencies, combined with visual cues, show meaningful promise. The combination of sound and light triggers automatic avoidance responses.

3. Habitat Management (Most Effective)

Removing bird attractants within 10,000 feet of runways is the most reliable approach. If birds aren't present, strikes cannot occur.

4. Active Hazing and Radar Monitoring

Real-time radar detection combined with acoustic hazing programs can dynamically manage bird presence during critical flight phases.

5. Operational Procedures

Timing flight operations to avoid peak bird activity periods and adjusting flight paths around known bird corridors reduces exposure.

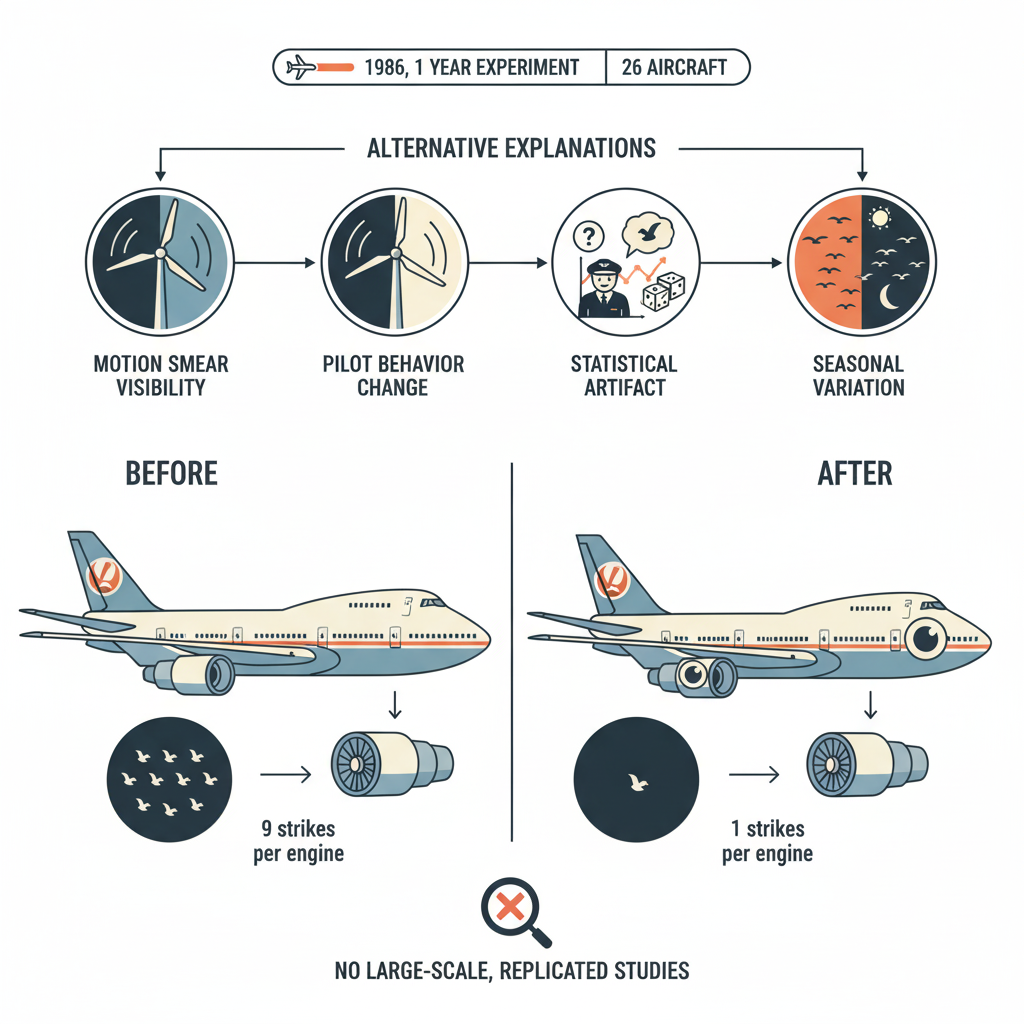

Part 6: The ANA Study—What Really Happened?

In 1986, All Nippon Airways conducted a one-year experiment, painting "wobbly ball"-styled eyes on 26 Boeing aircraft. Results showed a ~20% reduction in bird strikes.

Why might this have worked (if it did)?

Several alternative explanations are more plausible than "birds were scared":

Motion smear visibility: The painted eyes might have created contrast changes visible during rotation, similar to wind turbine blade painting (which reduces bird collisions by up to 70% through motion disruption, not fear).

Pilot behavior change: Knowing about the experiment, pilots or ground crews might have unconsciously taken additional precautions.

Statistical artifact: A reduction from 9 to 1 strike per engine over one year is a small sample size; random variation alone could explain the range.

Seasonal variation: Bird populations fluctuate by season; the comparison year might simply have had fewer migrating birds.

No large-scale, independently replicated controlled studies have definitively proven that engine painting prevents bird strikes.

Part 7: The Pedagogical Lesson

This exploration reveals a critical principle in aviation safety: intuitive solutions based on human psychology often fail when applied to non-human threats.

Painting a scary face makes intuitive sense to humans because:

We recognize faces and interpret them as threatening or friendly.

We make threat assessments based on visual information.

It fails in application because:

Birds lack the template to interpret painted faces as threats.

The temporal constraints of collision avoidance cannot be overcome by visual cues alone.

The neurobiological basis of threat recognition differs fundamentally between species.

The most effective deterrents work with bird biology, not against it, using lighting that triggers automatic avoidance responses, acoustic signals that activate innate fear responses, or habitat management that prevents encounters entirely.

Conclusion: Moving Forward

The next time you see a commercial aircraft with painted eyes or spirals on its engines, you'll understand the historical reasoning, but you'll also know it's not the real solution to bird strikes. The real solutions are more sophisticated, require operational integration, and address the fundamental problem: not what birds can see, but what they can process in the microseconds before collision.

Aviation safety has moved beyond painting scary faces. The industry now deploys radar systems, AI-driven bird detection, acoustic hazing, habitat management, and aircraft lighting specifically tuned to avian visual systems. These approaches are grounded in decades of ornithological and collision research, and they're delivering results.

For airport wildlife managers, pilots, and aviation professionals: Focus on habitat management, active hazing during critical hours, and operational procedures. For aircraft manufacturers: Invest in pulsing light systems and acoustic deterrents. The science is clear about what works and what doesn't.

The solution to bird strikes isn't making engines look scarier to humans. It's understanding birds deeply enough to build systems that respect their neurobiology rather than trying to trick it.

References:

Head Image source: https://metroairportnews.com/all-nippon-airways-says-eyeballs-painted-on-aircraft-cut-bird-strikes/

Seaworld.org - All About Raptors - Senses - https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-63039-y

Birdwatchingdaily.com - How Birds See in Slow Motion - https://www.aavac.com.au/files/2012-07.pdf

Royal Society Publishing - Avian binocular vision - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5371358/

Golden Gate Bird Alliance - How fast can birds see? - https://goldengatebirdalliance.org/blog-posts/how-fast-can-birds-see-4-7/

Martin & Katzir - Visual fields, foraging and binocularity - https://www.internationalornithology.org/PROCEEDINGS_Durban/Symposium/S45/S45.2.htm

Veterinary-practice.com - Importance of eyes in raptors - https://www.veterinary-practice.com/article/importance-of-eyes-in-raptors

Seaworld.org - All About Raptors - Senses - https://seaworld.org/animals/all-about/raptors/senses/

PMC - Critical Flicker Fusion Frequency - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8537539/

Illinois State - Visual fields and their functions in birds - https://about.illinoisstate.edu/vfdouga/files/2020/08/VisualfieldsandtheirfunctionsinbirdsJOrnithol2007.pdf

Wikipedia - Bird vision - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bird_vision

Wikipedia - Flicker fusion threshold - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flicker_fusion_threshold

ScienceDirect - Avian vision - https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982222010272

Birdwatchingdaily.com - How Birds See in Slow Motion - https://www.birdwatchingdaily.com/beginners/birding-faq/how-birds-see-in-slow-motion/

PMC - Wide-eyed glare scares raptors - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6181303/

PMC - Hawk Eyes I - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2943905/

USDA APHIS - Amplified bird-strike risks - https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/10-037%20Dolbeer-Increase%20in%20strikes%20above%20500%20ft%20BSC-USA_1990-2009_revised.pdf

Lund University - Raptor vision - https://portal.research.lu.se/en/publications/raptor-vision

Wikipedia - Wedge-tailed eagle - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wedge-tailed_eagle

PMC - Paint it black - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7452767/

PMC - Field testing an "acoustic lighthouse" - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8081207/

PMC - Contrasting coloured ventral wings - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9257291/

PeerJ - Evaluating acoustic signals - https://peerj.com/articles/13313

NIST - A quantitative approach to looming - https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/IR/nistir4808.pdf

Frontiers in Psychology - Emotion-gaze interaction - https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1414702/full

PLOS ONE - Effects of Vehicle Speed - https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0087944

PubMed - Changing In-Depth Visual Perception - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24858108/

PeerJ - Inefficacy of mallard flight responses - https://peerj.com/articles/18124/

ScienceDirect - Visual processing of looming - https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/004269899400274P

Precise Flight - On-Board Bird Strike Prevention - https://aeroaccess.ebizcdn.com/media/Precise_Flight_Pulselite_for_Bird_Strike_Reduction.pdf

Nature - Estimating the impact of airport wildlife hazards - https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-79946-3

RSIS International - Evaluating application of bird repellent technology - https://rsisinternational.org/journals/ijriss/articles/evaluating-the-application-of-bird-repellent-technology-in-in-flight-systems-insights-from-aviation-professionals/

FAA Blog - How Wildlife Strike Mitigation Helps - https://www.faa.gov/blog/clearedfortakeoff/no-fowl-play-how-wildlife-strike-mitigation-helps-ensure-safe-skies

ICAO - Final Report - https://www.icao.int/sites/default/files/APAC/Meetings/2025/2025%20APWHMWG7/1-Report/-Final-Report-of-AP-WHM-WG-7.pdf

UNL - Efficacy of aircraft landing lights - https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/context/icwdm_usdanwrc/article/1077/viewcontent/blac041.pdf

Airways Magazine - ANA Paints Eyeballs on Jets - https://airwaysmag.com/legacy-posts/ana-paints-eyeballs-on-a380s

Airways Magazine - ANA Paints Eyeballs on A380s - https://airwaysmag.com/new-post/ana-paints-eyeballs-on-a380s

AeroSavvy - Aircraft Engine Spirals & Swirls - https://aerosavvy.com/aircraft-engine-spirals/

SlashGear - Why Jet Engines Have Spirals On Them - https://www.slashgear.com/1916066/jet-engine-spiral-purpose-reason-explained/

Simple Flying - Why Are Spirals Painted On Aircraft Engines - https://simpleflying.com/why-are-spirals-painted-on-some-aircraft-engines/

FAA - Wildlife Hazard Management at Airports - https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/airports/environmental/policy_guidance/2005_FAA_Manual_complete.pdf

Interesting Engineering - White Spiral Marks on Aircraft Engines - https://interestingengineering.com/transportation/heres-why-airplane-engines-have-white-spiral-marks-on-them

Instagram - A Simple Paint Trick - https://www.instagram.com/p/DN5F2m4j788/